I came across this post on one of my favorite blogs – NextBillion. NextBillion is great resource for anyone interested in exploring opportunities to build sustainable businesses that positively impact (be it socially, financially, environmentally) the base of the economic pyramid (BoP). Grant Tudor’s blog post in particular caught my eye as I just finished reading The Power of Positive Deviance – a great book which describes how “positive deviants” or PDs see solutions where others do not and then tells first-hand stories of how PDs tackled and alleviated some of society’s toughest challenges.

-Mike Pezone

by Grant Tudor

The Millennium Villages Project (MVP), the brainchild of development economist Jeffrey Sachs, has set out to demonstrate ‘what success looks like’ in development. Armed with a five-year budget of $120 million and a suite of meticulous interventions – from importing seeds and fertilizers to teaching modern farming practices – the sweeping development project is ‘transforming’ 80 villages across Africa.

Meanwhile, a farmer named Yacouba Sawadogo has been experimenting with some manure. After adding in bits to zai, the shallow pits dug around crop roots to harvest rainwater, the seeds embedded in the manure have sprouted small trees – increasing crop yields, restoring soil fertility and ensuring food security. In the face of a warming climate and vast desertification across the Sahel, his unexpected version of tree-based farming has quickly spread; new greenery across Burkina Faso is now visible via satellite imagery.

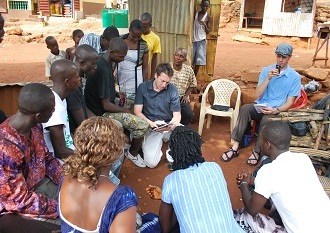

Researchers call individuals like Sawadogo – who demonstrate uncommon but successful behaviors – ‘positive deviants.’ While subject to the same resource constraints as their peers, they practice rare behaviors with dramatically better outcomes. Unlike the MVP, their solutions cost nothing; they avoid reliance on outside aid; and they mobilize what assets are already available. They exhibit a distinctly bottom-up approach to development – if their behaviors are found and spread.

Enter, marketers. Play-doh was originally produced as a wallpaper cleaner. Then, when some deviant nursery school children were spotted using it to make Christmas ornaments, marketers spread the new behavior like wildfire. Could we employ the same listening and amplifying approach to spread positive deviant behaviors for development? To bring rare but golden behaviors like Sawadogo’s to scale?

Take HIV prevention among injecting drug users (IDUs). A study of IDUs found that positive deviants in one locale simply bent their needles to prevent re-use – a startlingly effective behavior already being practiced by a clever few. So instead of limiting ourselves to a costly HIV awareness campaign to prevent needle sharing, why not also recruit some positive deviants in the IDU community to become peer educators?

Or take malnutrition. In 1990, 65 percent of Vietnamese children under the age of five suffered from nutritional deficiencies. A handful of children, however, were consistently doing just fine – despite living in the same impoverished communities. After observing the feeding practices of their mothers, researchers found that they were simply adding tiny shrimps, crabs and snails into food.

Save the Children worked with these positive deviants to spread the behavior. After one year, 80 percent of the program’s 1,000 children were well nourished. After several, a national program had impacted more than 2.2 million people. The approach stands in sharp contrast to the MVP, which advocates “introducing new, improved varieties of food” as central to its suite of nutrition interventions. New foods and imported behaviors are sometimes called for; but perhaps we could also do better to search out the deviants?

Might there be a few mothers who are always using clean water? A few households that consistently avoid malaria? A few kids who are never marked as truant? A few farmers who successfully irrigate during droughts? Positive deviance implores us to look for those who have already figured it out – those outliers that demonstrate low-cost, readily available and remarkably effective solutions – and market their behavior broadly.

The approach, however, risks being relegated to a basket of other “techniques” practitioners use in the field. Instead, it should be better understood as a development philosophy: solutions usually don’t need to be imported; often, the better behaviors and needed assets are already there. We just have to search for, study and amplify them. Most importantly, it tempers our inclination to believe we know the answer. Usually, we don’t. But if we search out the deviants, we’re probably closer to it.