Editors Note: This article was originally posted here by The Washington Post

A child living in a slum plays on a swing under a bridge on the bank of Bagmati River in Kathmandu October 17, 2011. (NAVESH CHITRAKAR - REUTERS)

At the United Nations, a new exhibit from the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum — “Design With the Other 90%: Cities” — highlights the types of innovations from developing markets that are improving the ability of citizens to live in densely-populated, urban environments where resources ranging from water to education are in scarce supply. At a time when the conventional wisdom holds that the flow of innovation is from the developed world to the developing world, is it really possible that any of these innovations — many of them specifically created for the world’s worst “slums” — will ever make their way to the United States?

Already, some areas of the U.S. might have more in common with the vast urban slums of the developing world than many of us might be willing to admit. (If you visit the exhibit at the UN, check your preconceptions at the door.) For example, in one of the maps created for the exhibit called Informal Settlement World Map — a team of researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Design mapped out the growth of slum households worldwide, based on five different criteria: inadequate housing, insufficient living space, insecure land tenure, lack of access to water and lack of access to sanitation. While the bulk of these “slums” are located in regions we might expect — Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and South East Asia — there are also glowing orange triangles of slums stretching from the California-Mexico border all the way to Texas and then up and down the Eastern Seaboard.

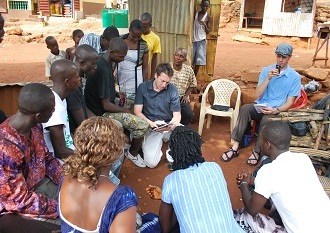

The UN exhibit showcases innovations that help citizens improve their access to basic necessities — including water, sanitation, food, health, transportation and education. There are also innovations that help marginalized groups — typically women and children — become included in the growth of these urban settlements. Two of the more well-known examples include the M-PESA mobile payment system, which originated in Kenya, and the Digital Drum, which offers almost a steampunk approach to technology — a recycled steel drum encasing a laptop computer, which is then powered by solar panels instead of electricity.

The UN exhibit showcases innovations that help citizens improve their access to basic necessities — including water, sanitation, food, health, transportation and education. There are also innovations that help marginalized groups — typically women and children — become included in the growth of these urban settlements. Two of the more well-known examples include the M-PESA mobile payment system, which originated in Kenya, and the Digital Drum, which offers almost a steampunk approach to technology — a recycled steel drum encasing a laptop computer, which is then powered by solar panels instead of electricity.

There are already potential takers in the world’s richest cities for these innovations. The Vertical Gym — originally created for the slums of Caracas, Venezuela — has been considered by local authorities in places like the Netherlands and even New York City, where these fitness facilities could be used for local public schools in cramped urban conditions. When one sees innovations like the Floating Community Lifeboats for schools, libraries and clinics in Bangladesh — one wonders whether these boats might ever be used by low-lying U.S. coastal areas in the wake of future, devastating hurricanes.

It is likely we will see some of these innovations implemented in the near future. After all, the first installment in the “Design for the Other 90%“-series brought us One Laptop Per Child and the LifeStraw. Without a doubt, the future trajectory of global growth over the next two decades is the urban mega-city, whether it’s on the East Coast of America or the East Coast of India. There are now 1 billion people living in “informal settlements” around the world and this number is projected to double within the next 20 years. Now, it is the choice of policymakers to decide how we accommodate this massive growth. Most likely, socially responsible innovators need to stop thinking in terms of the top 10 percent of the world’s population, and instead, re-shift their focus to the other 90 percent. In other words, they must learn how to slum it.