Put innovation at the heart of refugee protection work | Source: Alexander Betts, The Guardian, Jan 4, 2012.

Putting refugees in camps isn’t enough – harness their creativity and help them become self reliant and prosper

The traditional model of refugee protection is donor-state funded and prioritises keeping people alive. It is the international analogue to the domestic welfare state. This is often necessary during emergency. But all too often people get stuck in refugee camps for many years. Over 6 million of the world’s refugees are in so-called protracted refugee situations, with an average length of stay of 17 years – Somalis in Kenya, Eritreans in Sudan, Sudanese in Chad, Afghans in Iran and Pakistan, and Burmese in Thailand.

The existing humanitarian paradigm can be inefficient. It could fail to make use of the best products and processes available; prove unsustainable, requiring public money to be endlessly channelled into warehousing people; and may lead to dependency, often undermining people’s ability to help themselves. Instead, there may be alternative ways of doing refugee protection, which draw upon untapped resources or build upon refugees’ own skills, aspirations, and entrepreneurship.

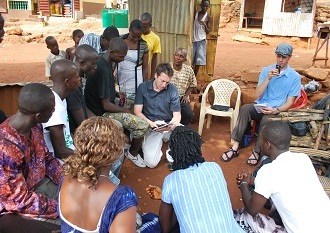

The Dadaab refugee camp, above, in Kenya where refugees have taken part in innovation workshops. Photograph: Sipa Press/Rex Features

Innovation is not about novelty or invention. It is about adapting to context. It is a methodology for change, often used in the private sector but, which is, with few exceptions, neglected in humanitarian work. It can be understood as a four-stage process: problem specification, looking for potential solutions, piloting those solutions, and scaling them where appropriate.

Innovation is highly relevant to refugees in at least two areas: the emergency phase, in which alternative resources may be available across humanitarian sectors (water and sanitation, health, shelter, and internet and communications technology, for example) and protracted situations, in which innovation may provide ways to move beyond encampment through creating livelihood opportunities and self-sufficiency.

Innovation may come from the creativity of refugees themselves. By definition, refugees have had to survive and adapt in entrepreneurial ways. Even in the most restrictive camp environments, like the Dadaab camps in Kenya, small businesses thrive, and SMS and Facebook are ubiquitous and adapted to create economic opportunity. In Uganda, where refugees have the right to work, the majority in Kampala are self-employed and in the Kisenyi district many Somalis run thriving businesses that even employ nationals. Access to remittances and the diaspora frequently provides the source of capital for entrepreneurship.

Yet such innovation is often constrained by context. Entrepreneurship might be better supported by partnerships that remove barriers. Training, mentoring, microfinance, and business incubation – through Refugee Innovation Centres, for example – could encourage self-reliance. A recent innovation camp held in Dadaab, supported by Microsoft and Safaricom, illustrates the potential.

Innovation appeals to private sector and could engage them in humanitarian work. If you can innovate for 43.5 million displaced people, you are effectively innovating for the bottom 2 billion people who live on less than $2 a day. That bottom of the pyramid innovation is where there is huge potential for growth, and offers an incentive for private sector engagement at every level – local, national, and even global. It is on this basis that UNHCR, for example, has adapted its private sector fundraising strategy to move beyond philanthropy and corporate social responsibility to recognise the potential of innovation.

We recently launched the Humanitarian Innovation Project, based at the Refugee Studies Centre at the University of Oxford, which is researching the role of technology, innovation, and private sector in refugee protection. The project is built in partnership with UNHCR Innovation and Return on Innovation, a US-based not-for-profit organisation. The aim is to develop a better understanding of the role that humanitarian innovation can play in creating more sustainable approaches to refugee protection.

So what is the way forward? A lot of existing work on innovation is mainly concerned with improving the work of NGOs and international organisations. A core aspect of our work is to identify and support grassroots innovation by refugees and find appropriate partnerships.

Research can contribute to this, but that isn’t enough. We are looking to set up a Refugee Innovation Centre in an urban or rural areawhere refugees can access training, mentorship and business opportunities. The hope is that, over time, a bottom-up approach to innovation will contribute to a refugee assistance model built more on sustainability rather than long-term dependency and encampment.

Dr Alexander Betts is lecturer at the Department of International Development, University of Oxford, and director of the Humanitarian Innovation Project.