This is a repost written by Archana Sinha who leads the Health and Nutrition Initiative at Ashoka India. This post first appeared first appeared here.

From human-centered design to the lean startup approach, methods to develop innovative products and services emphasize the importance of understanding what customers really need. Here are some lessons in innovation that social entrepreneurs have learned from empathizing with their customers:

Don’t let technology take the wheel: “I used to think that the problem lies in technology. What we realized eventually was that the problem does not merely lie in the technology, but the psychology,” says Ashoka Fellow Swapnil Chaturvedi in a recent video on his work.

Swapnil, founder of Samagra, is talking about providing adequate sanitation in India, where over 50 percent of the population defecates in the open. His statement could be true anywhere else in the world; toilets installed in low-income areas often fall into disuse or end up being used for other purposes such as vegetable peeling bins. To mitigate this, when designing community toilets in Pune slums, Swapnil introduced a LooRewards system. Based on a mapping of the community’s needs, this system linked toilet use with discounts on washing and sanitation products, water purification systems or fortified, nutritional snacks sold by local producers. This helped Samagra engage over100 first-time users of toilets.

Michael Murphy, co-founder of the MASS Design Group also realized that sophisticated technology wasn’t essential, while designing the 140-bed Butaro Hospital in Rwanda. He reveals, “A common misconception is that design interventions that combat the health worsening effects of hospitals are more expensive or require advanced equipment and machinery, but we’ve seen that’s not the case. Hospitals all over the world can be harsh environments for patients—which is shocking to consider, as we think of hospitals as places people go to get better. But labyrinthine corridors, harsh lighting, and stale air can in fact jeopardize a patient’s capacity to heal. Beyond that, hospitals are actually making people sicker. According to the CDC, about 1 in 20 patients gets a hospital-acquired infection (something they did not arrive with) per year in the U.S. (CDC, 2013). In Butaro, we designed the building without hallways, instead creating open-air, comfortable waiting spaces that would reduce the transmission of infection, but still provide opportunity for check-in and interaction. MASS also incorporated ample landscaped areas for patients to have quiet space outside, or visit with their families.”

Build the solution for the most under-served customers: Your most engaged customers often come from the edges of the market. Swapnil admits, “When I started working on community toilets, I didn’t know women would become our biggest customers. However, we have observed that in urban areas, where everyone is stretched for land and privacy, men find a solution to the lack of toilets, but women can’t. They hold their urine and bowel movements, resulting in urinary tract infections.” Thus, women are keen users of Samagra’s community toilets and as its most vocal customers, they help get their friends and families to sign up. Samagra, in turn, pays special attention to their needs, by providing dustbins in each toilet stall for disposing sanitary napkins and prioritizing water supply in the women’s toilets.

Shift how the community sees you: “Hospitals should be, first and foremost, a public resource. This includes making the hospital an approachable space, where people can come to maintain their quality of life as well as receive acute care. That is why a lot of the spaces are landscaped,” asserts Michael. While building the hospital, he sought to expand its benefit beyond healthcare. “Health infrastructure requires massive investment and construction. This mobilization of resources should be transferred to the local community, by using local labor and materials, as well as providing on-the-job training. Butaro employed over 4,000 people, and transferred a few million dollars into the local economy as well. Beyond that, several masons trained at Butaro have gone on to other skilled jobs,” he states.

Focusing on positive outcomes for the community has prompted Swapnil to transform his rewards program from what he calls “transaction-based rewards” to “value-based rewards,” such as discounts on private tuition classes for schoolchildren. Samagra’s toilets also have bank kiosks that allow customers to deposit small amounts in their bank accounts regularly. This shift has resulted in increased revenue for Samagra, as “learning what customers care about through empathetic market research has allowed us to capture value and monetize it.” Transforming toilets into community connectors that allow slum-dwellers to access a broader range of services is powerful. Swapnil shares, “Since we installed a banking kiosk in the community toilets, rather than a place to relieve themselves, the toilet becomes a place to bank. People will never vandalise their bank; we’ve seen vandalism reduction by 85%. The toilet has become a place of business and a community centre of sorts.” Regular savings also allow customers to budget for the fees for using the toilet, and their payments have become more regular.

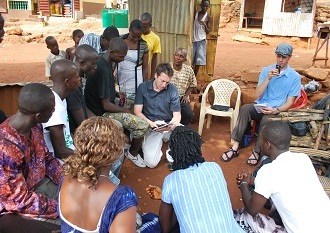

Innovations driven by empathy are now enabling Swapnil and Michael to expand the scope of their work. Michael’s MASS Design Group is currently completing construction on both a tuberculosis hospital and a diarrheal disease treatment center in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, as well as designing maternity waiting homes in Malawi and a Center for Global Health at Mbarara University in Uganda. Swapnil’s Samagra is evaluating options for adding more value-based rewards such as day-care centers for mothers who work in the informal sector and can’t afford to quit their jobs to take care of their children.